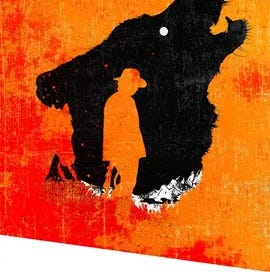

The Crossing, 30 years on.

One of Cormac McCarthy’s bleakest novels turns 30 this year. Note: This review contains spoilers.

Deep in each man is the knowledge that something knows of his existence. Something knows, and cannot be fled nor hid from.

---

He said that most men were in their lives like the carpenter whose work went so slowly for the dullness of his tools that he had no time to sharpen them.

---

The Crossing is an enigmatic novel. At times incredibly repetitive—almost boring— occasionally impenetrably philosophical, often achingly beautiful, and finally, completely heart-breaking. It is the second novel in Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy. But where the first novel All the Pretty Horses was succinct, romantic, funny, and violent, The Crossing is long, bleak, lonely, and still also violent (as McCarthy’s works usually are).

Among fans, The Crossing is one of the more controversial works of McCarthy’s Southern era. The unfavourable reviews are not without merit; though McCarthy (who passed away last year) is rightly considered one of the all-time great prose writers, some of his worst habits are also on display in this book. However, the emotional impact of the first third of the novel, the handful of truly arresting scenes interspersed throughout the middle section, and the absolutely crushing ending make this a novel which will still stand on its merits for a long time.

It is not a light-hearted novel. This quote from All the Pretty Horses holds true for the ignorance of readers about to start The Crossing:

“He said that it was good that God kept the truths of life from the young as they were starting out or else they’d have no heart to start at all”.

Set in the early 1930’s in the American Southwest, The Crossing tells the story of Billy Parham’s repeated crossings between America and Mexico. When a she-wolf crosses from Mexico into New Mexico and begins killing stock on the Parham property, teenager Billy and his father begin the difficult and dangerous task of tracking and trapping her. After a battle of wits in which the wolf repeatedly turns up their traps and kills more stock, Billy finally outsmarts the wolf, and catches her in a trap. What follows is a riveting scene in which Billy uses an ingenious method to subdue her, tie her mouth, and leash her. He then mounts up and inexplicably leaves his family without a word, setting off on a long journey to return the wolf to the mountains of Mexico. Thus begins his first crossing.

On the six-day journey to Mexico, Billy and the wolf form an uneasy understanding which, eventually, becomes an emotional bond of some strange sort. In scenes tender yet brutal, Billy has to coerce and manhandle the wolf, sometimes dragging her along behind his horse, or letting her exhaust herself writhing and fighting at the end of the leash. He repeatedly pins the wolf down and pours water in the side of the makeshift muzzle so she can drink water and rabbit blood, and eventually he alters the muzzle so he can feed her small pieces of Rabbit meat. Eventually the wolf learns to capitulate.

Minus the sense of foreboding, this first section of the book—the first crossing—starts with a similar romanticism to All the Pretty Horses, and one feels that though this is still a McCarthy novel, we may not be in for too harsh a journey.

“The new country was rich and wild. You could ride clear to Mexico and not strike a crossfence. He carried Boyd before him in the bow of the saddle and named to him features of the landscape and birds and animals in both Spanish and English. In the new house they slept in the room off the kitchen and he would lie awake at night and listen to his brother’s breathing in the dark and he would whisper half aloud to him as he slept his plans for them and the life they would have.”

It’s no Old Yeller or Where the Red Fern Grows, but it still feels somewhat innocent–the story of a young cowboy on a journey with his wild-pet wolf. McCarthy gives us a few haunting scenes from the wolf’s perspective, echoing the beloved tales of Jack London. There are quiet, intimate scenes in which Billy and the wolf sit opposite each other over a fire, Billy talks and sings to her, and one can sense their uneasy trust growing. Their encounters along the way with other locals have a charming humour to them:

“Boy what’s wrong with you? That thing comes out of that riggin it’ll eat you alive.

Yessir.

What are you doin with him?

It’s a she.

It’s a what?

A she. It’s a she.

Hell fire, it don’t make a damn he or she. What are you doin with it?

Fixin to take it home.

…

Have you always been crazy?

I don’t know. I never was much put to the test before today.”

But there are also hints of what is to come. Before Billy sets off to Mexico, he and his younger brother, Boyd, encounter a threatening “Indian” on their property who demands food and rudely questions them about their weaponry and their homestead. Boyd also has apocalyptic dreams about people immolated on a dry lake bed. These scenes of foreboding, however, go somewhat forgotten for the beautiful scenes of country life, trapping, and wolf-taming. McCarthy’s singular combination of declarative mundanity and existential, alchemical prose is always on display:

“He held the trap up and eyed the notch in the pan while he backed off one screw and adjusted the trigger. Crouched in the broken shadow with the sun at his back and holding the trap at eyelevel against the morning sky he looked to be truing some older, some subtler instrument. Astrolabe or sextant. Like a man bent at fixing himself someway in the world. Bent on trying by arc or chord the space between his being and the world that was. If there be such space. If it be knowable. He put his hand under the open jaws and tilted the pan slightly with his thumb.”

Upon crossing into Mexico, a group of locals harass Billy and confiscate the wolf. Having formed a deep bond with the wolf and feeling responsible for her (he is now aware that she is carrying pups), Billy follows them only to discover that she is being used in a dog-fighting ring. After watching the wolf endure round after round of fighting—realising she is horribly wounded and that there are still more dogs to come—Billy steps through the crowd and shoots the torn and bloody wolf himself. After some tension and a near shootout, the crowd watches as Billy, distraught, picks the wolf up and walks out into the night. He takes the wolf into the mountains to bury her, and in an incredibly bleak image, McCarthy describes the pups in her stomach crying out in confusion as the cold draws in around them.

“He’d carried the wolf up into the mountains in the bow of the saddle and buried her in a high pass under a cairn of scree. The little wolves in her belly felt the cold draw all about them and they cried out mutely in the dark and he buried them all and piled the rocks over them and led the horse away.”

This first section of the book is one of the most affecting pieces of literature I have ever read. It’s a romantic tale of boyhood, masculinity, empathy, nature, and adventure, which ends with an absolutely devastating loss of innocence. As a stand-alone novella, it would have been one of the best ever written. However, the novel continues for another 250 or so meandering pages, and though the new tone has now been set for the novel, it is often disjointed. It is still largely satisfying, though, and we get the usual themes we expect from McCarthy: modernity and masculinity, violence and nature–and its all dealt with in his signature style.

“When he walked out into the sun and untied the horse from the parking meter people passing in the street turned to look at him. Something in off the wild mesas, something out of the past. Ragged, dirty, hungry in eye and belly. Totally unspoken for. In that outlandish figure they beheld what they envied most and what they most reviled. If their hearts went out to him it was yet true that for very small cause they might also have killed him.”

After burying the wolf, Billy returns to his farm to find his parents have been murdered (likely by the threatening “Indian” encountered earlier), their horses stolen, and his little brother, Boyd, has been put into foster care. This is the point at which the story begins to meander and becomes only loosely plotted. Billy rescues Boyd from care, and the two set off for Mexico again, to retrieve their family’s stolen horses. This is the second crossing.

The brothers love each other deeply, but along their travels their relationship becomes strained. Billy is wracked by guilt (it may be that their parents were murdered because Billy had taken off to Mexico with the family rifle). Mishaps and adventure occur, but also plenty of McCarthy’s signature descriptions of riding-and-camping, eating beans and tortillas; more riding-and-camping, more eating beans and tortillas. Additionally, McCarthy’s complete abdication of interiority in his writing makes the boys’ behaviour often puzzling to the reader. One must be adept at reading between the lines to understand why the characters do what they do. Eventually they retrieve their stolen horses, but Boyd falls in love and decides to stay in Mexico. Billy travels back to America, works odd jobs and attempts to join the war, though he is denied due to a heart murmur.

Billy saves enough money to equip himself for his third crossing–to bring his brother home to America. However, it is not to be as Boyd has been killed, so the journey devolves into McCarthy’s twist on Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and the final section of McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove. Billy exhumes his brother’s remains and travels home to America to bury him.

Over the course of these second and third crossings, Billy encounters numerous older characters who have lived through tragedy, war, and revolution. They often feed him and engage him in long dialogues, which form discrete stories-within-a-story, reminiscent of those seen in Moby Dick or the novels of Dostoevsky. There are extended discussions on life, war, revolution, epistemology, history, myth, and meaning. Some of these are overly long and arduous, especially because of McCarthy’s tendency to write pieces of dialogue in untranslated Spanish (for this reason, a kindle is the best method for reading McCarthy, in my opinion–it comes with a translate option).

One particular dialogue tells a harrowing tale which stays with you long, long after the book has ended. In this scene Billy sits with a blind man who tells the time “by turning his face to the sightless sun like a worshipper”, and learns how the man lost his eyes to a sadistic Federal officer named Wirtz, during the Mexican Revolution. The method of his blinding is horrifying and shocking–an incredibly confronting scene which I won’t fully spoil here.

“And so he stood. His pain was great but his agony at the disassembled world he now beheld which could never be put right again was greater. Nor could he bring himself to touch the eyes. He cried out in his despair and waved his hands about before him. He could not see the face of his enemy. The architect of his darkness, the thief of his light. He could see the trampled dust of the street beneath him. A crazed jumble of men’s boots. He could see his own mouth…

They tried to put his eyes back into their sockets with a spoon but none could manage it and the eyes dried on his cheeks like grapes and the world grew dim and colorless and then it vanished forever.”

Finally, after Billy has lost everything, after he has endured his three crossings and returned to America, McCarthy gives us another one of the most haunting scenes in all of literature. As Billy, now essentially homeless, settles into an abandoned building for a small dinner and a night of rest, an abandoned dog tentatively approaches him. It arouses something in Billy—shame or guilt, some memory of the wolf and what he gave up by caring for her. He attacks the dog and chases it off.

“The dog raised its misshapen head and howled weirdly. He advanced upon it and it set off up the road. He ran after it and threw more rocks and shouted at it and he slung the length of pipe… the dog howled again and began to run, hobbling brokenly on its twisted legs with the strange head agoggle on its neck. As it went it raised its mouth sideways and howled again with a terrible sound. Something not of this earth. As if some awful composite of grief had broke through from the preterite world. It tottered away up the road in the rain on its stricken legs and as it went it howled again and again in its heart’s despair until it was gone from all sight and all sound in the night’s onset.”

Billy then goes to sleep, and later he awakes to what seems almost like the desert noon, but “there was no sun and there was no dawn”. The light he awoke to rapidly fades again, “drawing away along the edges of the world”, back into the darkness of night. A strange wind is sucked down off the mountains behind him. This scene is eerie and strange, but will be completely indecipherable to most readers, as it was to me, for many years. I recently found out that in this scene Billy is likely witnessing the effects of the Trinity Test, the first ever test of a nuclear weapon. The timing and location of the scene in the story corresponds to the date and time of the Trinity test, which occurred just before dawn in July 1945, in New Mexico. So, as the protagonist symbolically sheds the last of his innocence and abuses a dog in what is a heart-breaking antithesis to the story’s inciting incident, humanity perhaps does the same, entering the atomic age.

This strange false sunrise also triggers something in Billy—perhaps he realises what he has finally lost in that moment, how much he has changed—and he runs into the street and desperately calls for the dog, but it does not come:

“He called and called. Standing in that inexplicable darkness. Where there was no sound anywhere save only the wind. After a while he sat in the road. He took off his hat and placed it on the tarmac before him and he bowed his head and held his face in his hands and wept.”

Just when you think the charges against McCarthy as a nihilist might be true, after three hundred-plus pages of loneliness and grief and loss, McCarthy then leaves us with what is perhaps, in an understated way, the most optimistic line in his entire corpus. A reminder that no matter how much has been lost, how many mistakes made—in the atrocities of war and revolution; in the 79 years since the trinity test; in the thirty turbulent years since the novel was published; no matter how much we have lost or ruined in our own lives, the sun also rises on a new day:

“…he bowed his head and held his face in his hands and wept. He sat there for a long time and after a while the east did gray and after a while the right and godmade sun did rise, once again, for all and without distinction.”